What Chaos Can We Toss? What Past Can We Love?

Andrade's Souvenir of the Ancient World, Chaos, Ongoingness, and Tossing Stuff You Don't Want People to Read After You Die

There’s a soft-sided suitcase sitting in the middle of my little office. It’s in my way, and I’m not crazy about looking at it. It’s full of letters and keepsakes from the late 70s to the 90s that I’ve hauled around unopened for decades.

Last week, I lugged the case— pale yellow, vintage but not nice, POD scrawled on it in black Sharpie—up from the basement during a cleaning trance. I was in the thick of the kind of choring you do to keep the panic at bay. The suitcase presented itself as just another task. Why not dive right in, I thought. Make room. Clear space.

For a week, I avoided the contents of the suitcase because I’m wary around my younger self. But I’ve had persistent questions about home and loss, aging, and what people leave behind, etc. circling my head like a halo of tired, loyal birds. What mental and physical stuff is worth keeping? What would I want to save if my home were disappearing into rubble or ash, instability or misfortune? I wondered if the things inside that case might give me a tangible answer.

*

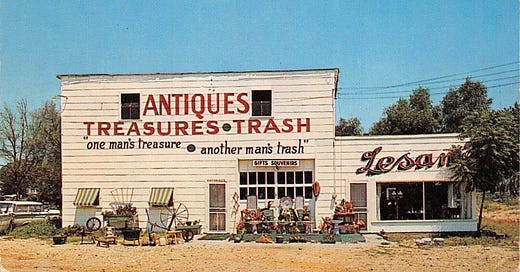

Sentimentality is like ether. It can put you to sleep while it’s also setting things ablaze. Whether we’re feeling precious and protective about junk in the basement or wistful about imagined better times, sentimentality can tip into magical thinking. Like the great Gladys Knight said, “Well…everybody’s talking bout the good ole days, the good old days…” Talking about good old days in a hazy, lazy, unchecked way can sharpen vague yearnings and emptiness into ill will, envy, and zero sum grabbing.

If I get lured away by the smell of a trick pie in beckoning cartoon hand form, I’m not home to mind the store. (Besides, it’s not a real pie, it’s a cliff.) Minding the store seems important right now. I don’t want to be a deluded person, un-useful in this moment while fancying a misremembered past, all weighted down with unchecked stuff in the basement, but bats in the belfry. So I press stuff into my kids’ arms on their way out the door after they visit. Here’s a coffee maker, a juicer, a prayer flag, pint glasses, perfectly fine scatter rugs, duplicates of photos, such a nice blouse, cookbooks. Take this, I don’t need it, don’t you need it, won’t you use it, you’ll use it, take it.

On an episode of Miss Scarlett (female detective) the other night, they were combing through some guy’s stuff post-mortem like a wrecking ball. I don’t want my kids going through my unvetted stuff after I die, so I opened the suitcase and started vetting. We’re each responsible for our own sentimentalizing, our own un-etherizing. So:

There were love letters from a serious boyfriend who died a few years ago in Denmark. I regret not going over to say goodbye. His sisters said he wouldn’t want me to see him like that. I love his sisters. I still wonder, though.

And letters from five or six close friends I’m no longer in touch with, all with allusions and specificity that characterize the blow-by-blow correspondence of people who have a dense and layered history: And you know how you-know-who can be…I ended up not getting that shirt…

I found four “This is my last letter” letters from a turbulent boyfriend, and a couple breezy ones from male letter-writers I don’t remember, even though it was clear from the letters’ contents that I had indeed known them.

And letters you get from your parents after you leave home, their handwriting familiar from birthday cards and notes about stirring the spaghetti. One letter from my mother apologized in advance for anything my first therapist would unearth and blame her for. Don’t they always blame the mother? I didn’t.

I found artifacts like the wedding invitation of my gymnastics coach to the woman he went on to murder a decade later. I tossed that one into the trash bag like a hot potato, and called it quits for that day.

There was an “ERA!” button, a large keychain fob that asked “Donde estan mis putas llaves?” and a welcome volunteer pamphlet from John Anderson’s campaign. There were business cards from job interviews, Pez containers, lip smackers, and concert tickets: Boomtown Rats, The Who, Jim Carroll, Patti Smith, The Kinks.

I got less sentimental with each pile, and started moving things along: toss toss toss. I put keepers into a smaller hard shell vintage suitcase. It says “Going Places” and has a picture of an old fashioned girl throwing her head back in laughter, skipping ahead.

The next morning at dawn, I was outside at the trash bin intending to dig out the cast-offs. But the bin was full, my bag of stuff was already at the bottom, and dog poop bags dotted the top like sentries to the past.

*

Long arcs of time and consequence give us context whether we want it or not. This Andrade poem balances its own quiet chaos with the comfort of ongoingness and implicit reassurances of resilience: The poem is here. You’re here. We’re still here.

Souvenirs of the Ancient World

Carlos Drummond de Andrade (trans. Mark Strand)

Clara strolled in the garden with the children.

The sky was green over the grass,

the water was golden under the bridges,

other elements were blue and rose and orange,

a policeman smiled, bicycles passed,

a girl stepped onto the lawn to catch a bird,

the whole world—Germany, China—

all was quiet around Clara.

The children looked at the sky: it was not forbidden.

Mouth, nose, eyes were open. There was no danger.

What Clara feared were the flu, the heat, the insects.

Clara feared missing the eleven o'clock trolley:

She waited for letters slow to arrive,

She couldn't always wear a new dress. But she strolled in the garden, in the morning!

They had gardens, they had mornings in those days!

- 1976 Brazil during or just before WW II, in the morning, in a garden. It’s lovely, and also something is off. In the first Wonka-vibe stanza things are the wrong color, but the colors are so pretty! There’s Clara and she’s strolling with children, so we stroll along with the rhythmic certainty of the lines and sentences. We’re not suckers, though; we know something dark is afoot. Former prohibitions are lifted in premonetory, self-redacting riddles. (Look up. It’s not forbidden.) Some girl is stepping onto the lawn to catch a bird. Plus, it’s too quiet. Later there’s fear and no new dresses.

Finally, the poem tells us, it’s all from days bygone! Like all souvenirs. But, again, the poem remains, and we’ve already been invited in. There’s resilience in that, like there is in this recent Robert Pinsky essay where he tackles impossible history.

*

After downsizing from POD to “Going Places,” I know that some stuff is important enough to keep lugging around: The things that situate you in time, place, and sequence. Notes with your father’s handwriting. Curiosities that keep you honest: What happened to those friendships? Did you stick with things too long or not long enough? Where did Maggie H. go? Who the hell was Fred Butkis?

Whether ancient or just old, remembered things can place us, without sentimentality or deal-making with the past. I think about history and patterns of suffering and loving, all happening, right now. There’s my sweet angel dog Hank dying, and a puppy next door yipping. There’s my son’s laughing, and families fighting, and my daughter teaching in the same place I did. There’s chicken marbella, and hand holding. Vital jobs lost, people crossing busy city streets safely, dates kept, sad texts, bad news, and babies latching on and nursing. All of it.

It’s ongoing, as are we. We don’t “just” keep going. But we do keep going. I think of this scene at the end of the novel Siddhartha where Govinda sees a stream of images pass over Sid’s face. It’s trippy, and rich with yes…and empathy for the predicament of human suffering:

He saw all these forms and faces in a thousand relationships to each other, all helping each other, loving, hating and destroying each other and become newly born. Each one was mortal, a passionate, painful example of all that is transitory.

There’s no minimizing the scale of the particular suffering that’s here with us right now, and coming. Hunger, disease, unsteady peace, big promises broken, hate in the name of god. Funding for a good project is at risk because what was required yesterday is forbidden today. A kid in school won’t get the disability services they need, and shame will be the result. Shame all around. Vets in care won’t have the lives or the good deaths they deserve. Many people won’t.

I’m trying to keep a clear eye on the chaos inside me and out. I keep checking for optional chaos I accidentally or carelessly invite in. When my chest is a churning mix of nostalgia, alarm, and anger, these things help me: Looking for and listening to wise elders, skiing in the woods, reading, cuddling Hank. Keeping heart. Walking forward. Titrating the news. Taking care of my people and other people’s people. Feeding them. Exclaiming and using exclamation points. Looking up. (It’s not forbidden.)

*

To beautiful Hank, 2/14/16-2/20/25. We will love you forever. And ever.

Souvenir of the Ancient World. Published by Antaeus Editions, 1976. Translation Mark Strand.

Excerpted from Looking for Poetry by Mark Strand, 2002.

Siddhartha by Herman Hesse, 1922, Guttenberg version

A Song on Porcelain. Robert Pinsky. The New Yorker, Jan. 30, 2025

Great!

Wow this is so great. Thank you toiling away so hard on it and sharing it with us!