I used to have a Kill Your Television bumper sticker on my VW Fox. Now I like TV, so it’s good I don’t have that car anymore. One hazard of having old friends is that they’re happy to remind you of a lifetime’s arc of inconsistencies.

About TV, my rule is that after I watch the news or some other destabilizing thing, I have to watch what my son calls a wholesome show. So, CNN or Frontline would be followed by Miss Scarlett (Female Detective) or All Creatures Great and Small. My world view skews dark, and it’s hard to get moving without strong and regular proof of good. Please send over any reminders of care and joy hiding in plain sight. Like this:

Filling Station by Elizabeth Bishop. Oh, but it is dirty! —this little filling station, oil-soaked, oil-permeated to a disturbing, over-all black translucency. Be careful with that match! Father wears a dirty, oil-soaked monkey suit that cuts him under the arms, and several quick and saucy and greasy sons assist him (it’s a family filling station), all quite thoroughly dirty. Do they live in the station? It has a cement porch behind the pumps, and on it a set of crushed and grease- impregnated wickerwork; on the wicker sofa a dirty dog, quite comfy. Some comic books provide the only note of color— of certain color. They lie upon a big dim doily draping a taboret (part of the set), beside a big hirsute begonia. Why the extraneous plant? Why the taboret? Why, oh why, the doily? (Embroidered in daisy stitch with marguerites, I think, and heavy with gray crochet.) Somebody embroidered the doily. Somebody waters the plant, or oils it, maybe. Somebody arranges the rows of cans so that they softly say: esso—so—so—so to high-strung automobiles. Somebody loves us all.

Bishop’s poem proves what I need proven when I need it, which is often. But the poem is no yes man. It doesn’t shush us with “oh there, there now.” Instead, it mandates humble and sharp witnessing of care and holiness, without cleverism or dismissal. It starts off clever and blunt and at a protective distance from the subject, but it goes out in bareness and awe. Our speaker enters the world of the filling station seeing dirt and filth, and progresses to sidelong (but then just plain old) wonder.

I figured that if I need regular reminding about why to bother and such, then you might too. So I got the poem from my Favorite Poems binder and kept it out on my desk. One night re-reading it before bed, I remembered something that happened to me— a time I got caught off guard by the simple genius of care. Strange to have forgotten it until now. It was back in my mid-20s. Still, though.

*

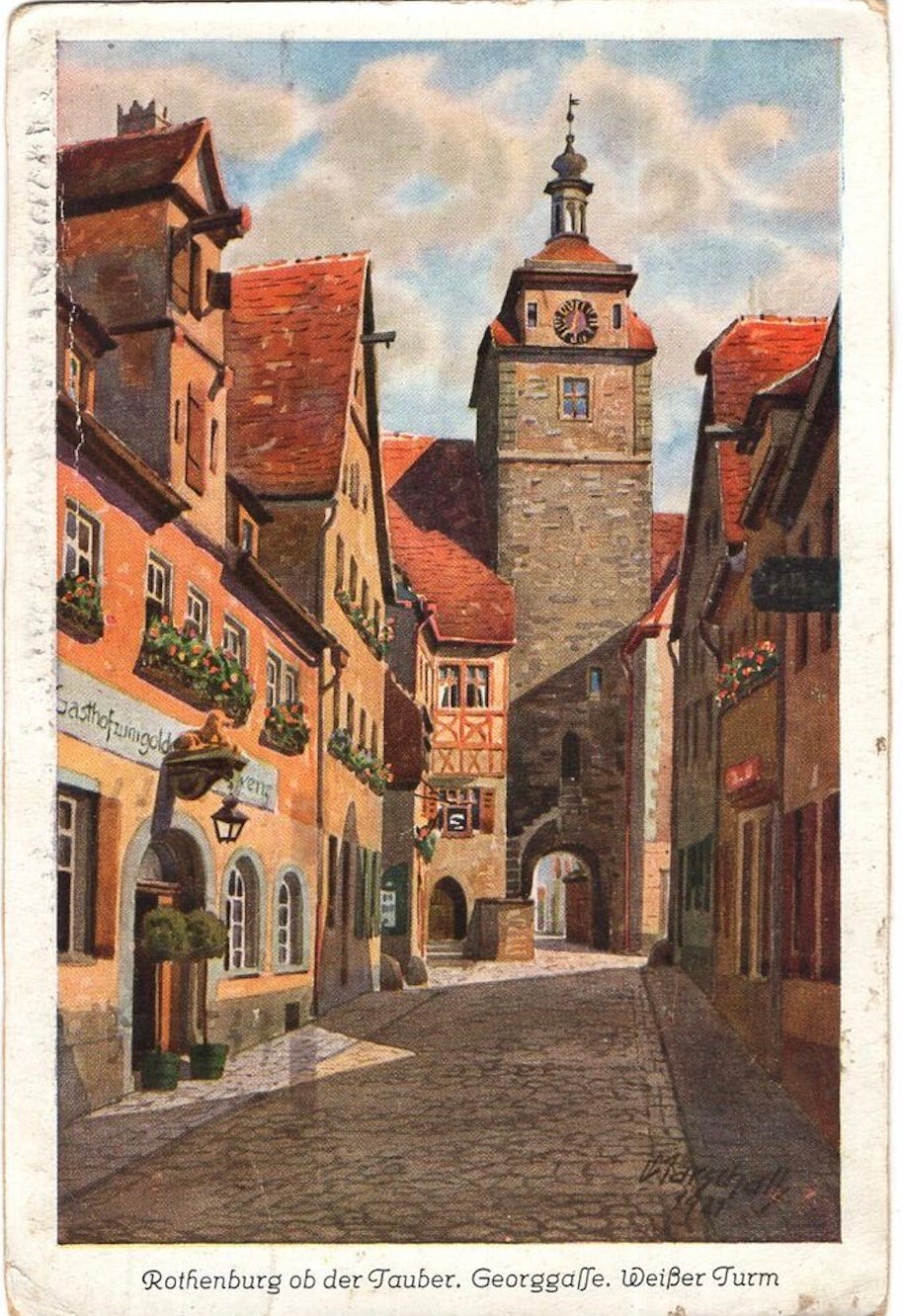

Julie and I were waiting to catch the last bus out of a medieval Bavarian town called Rothenburg Ob Der Tauber. After a few hours roaming the fairy tale streets, we were ready to not be there anymore. The town charmed and spooked us the same way fairy tales do: At first, you delight in the atmospherics of the whole scene—in this case, the rows of primary colored dwellings and apple cheeked citizens with mustaches and baskets of sweets. Then you notice there’s something dark lurking around the edges of the story, like there’s a catch—a subtext, disclaimer, or condition coming into focus. Maybe a lesson learned too late. Something about the cost of hubris or animus. Whatever it was, the air in that town felt heavy. Plus all Julie and I could afford was a pretzel and an apple strudel and a coke.

We showed the bus driver the address of a hostel we’d found in our book, and he nodded. The bus carried us beyond the tall walls that have protected the ancient town over the ages. Rothenburg didn’t get bombed away at the end of WWII. Despite the fog of war, a few people remembered that if we can leave beautiful things behind and intact, we should. So they did. This knew that this perfect example of a little German town deserved to be saved, not for the Nazis who had been its most misguided preservationists, but for humanity’s sake. For the rest of us.

Julie and I sat right behind the driver and looked over his shoulder into the dark for our hostel. We were the only passengers left on the bus. Finally, the headlights spotted a crooked sign on the edge of some brush and thick woods. The driver looked at us in his rear view mirror and said Geschlossen and kept driving. We figured he must have another place in mind, and he did.

We pulled up to an empty bus station and saw a woman standing up on a landing. While climbing the stairs with our backpacks, we realized that the driver lived with his family above the bus station. We’d be staying the night with them.

Our room had just a twin bed and a doorless closet with a very small pink coat and some little gray boots. At dawn, Julie and I walked out to the family’s narrow kitchen to see that they’d laid out quite a spread. Best plates, jams, breads, meat and bitter coffee. The father mimed that they’d already eaten, so the two of us sat and chewed while their young son and toddler daughter watched from behind their mother. The unexpected intimacy of the whole scene seemed to make all of us shy. The dad turned on the radio, to the BBC. Then the mother packed lunch sacks for me, Julie, and the father, and the three of us walked down the stairs. We were the first to board the first bus out that morning.

*

There are kindnesses that can prop us up and keep us going for some time. There are forces for good working among us. Sometimes they’re behind the scenes, or not in the form you’d expect. God in drag, as Ram Dass used to say. I tell myself to be on the lookout, especially when the evidence to the contrary seems so much easier to find and carry around like a sack of low hanging fruit.

I try to remember, and it’s getting harder. I write things down. I try to write everything down. Because the faultiness of my short term memory is proving to be a feature and not a bug, I think it’s likely I’ll forget more and more (genes, concussions, the 80s). If I could choreograph my own memory loss, I’d wish for a looping slideshow with images of care that would be the stubborn last ones to go.

I hope I remember, for example, the look of deep concern on a dog’s face when they’re looking at you when you’re crying. Or any look on a dog’s face. Any dog. Any look.

I hope I remember the heart attack that didn’t kill, and the doctors that made that so.

And the miracle boy, my high school student who lived alone but got himself to school on time and read every assigned story even when none of the other kids did. (Raymond Carver was fine, he told me, but he’s no Flannery O’Connor.) The boy wore one of three clean heavy metal t-shirts to school every day and had good friends. I hope I remember that boy and the other miracle people.

I hope I remember the births of my children. Chicken pot pie, warm and waiting. The big carved rocks in Dogtown. The bus driver. All the doilies and the rhythmic cans and places left just so, and soothing things and dark fairy tale places.

I hope I remember somebody loves us all. I really hope so.

P.S.—

Copyright Credit: Elizabeth Bishop, “Filling Station” from The Complete Poems, 1927-1979. Copyright © 1979, 1983 by Alice Helen Methfessel. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, LLC, http://us.macmillan.com/fsg. All rights reserved.

Source: The Complete Poems 1927-1979 (Farrar Straus and Giroux, 1983)

My love, I am at the New Orleans airport and I just read your substack, and I am quietly leaking tears. If I take a deep breath, it could be a sob. Oh shoot, here it comes. This so captures the life I want to live - the one where we don’t just focus on the doilies and the bus drivers but that we are the ones setting the doilies under the oil cans and setting the table for the lost travelers. This one hit me right in the heart. I LOVE LOVE LOVED it xoxo

We watch Call the Midwife to get us out of a glum mood. It’s always so amazing to see new life; it brings a smile.