I Am Me, and We Are We

Awakening to Our Somebody-ness, Falling Off Cliffs, and Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “In the Waiting Room”

Why should I be my aunt, or me, or anyone? - from In the Waiting Room, Elizabeth Bishop

When my daughter was about four, we were backing out of our driveway when she gasped like she’d found something important or realized she’d lost it. It was an adult sound. I put my foot on the brake and looked in my rearview mirror.

What’s wrong, Abby? What is it?

I’m a person. she said, accentuating person like person was a brand new idea.

What do you…um…You are. A person. I said something like that and kept my foot on the break and waited for what would come next. She was sitting in her carseat looking out the window, frowning and soft-focusing on something I couldn’t see. Was she even talking to me?

I’m a separate person. I put the car in park and turned around. Abby was patting her arms up and down, like she was frisking this new idea of herself, like she wanted to make sure she was still there.

Everyone’s a person. All separate by themselves. We were gonna be late.

That’s very true honey. I looked at the funny outfit she’d picked out that morning. I looked at her, this separate person who was also my person, and hoped she wasn’t having a scary out of body experience like the time she fainted when my friend Terri yanked a bandaid off her little leg. I dug around my bag for a juice box and wondered whether her sense of the world was unraveling or expanding, and what I should do and say.

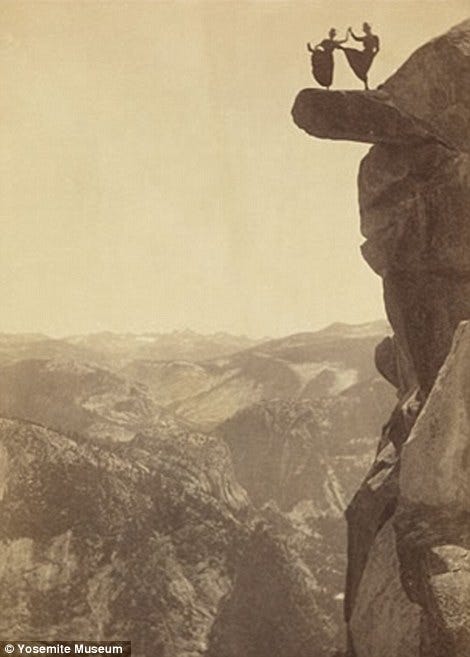

I thought about the time in Barre, Massachusetts in my 20s when I felt myself untethering on my meditation cushion during a long, advanced retreat I had no business being on. The scene that day in the meditation hall would have seemed serene to anyone peering in a window from outside: Neat rows of cross-legged people in a silent dusk lit room that smelled like both new and old wood. On the inside, though, in the dark behind my eyes, I felt myself falling off a cliff.

Later, when I reported this unsettling experience to the head meditator by way of explaining why I was going home two days early, she said people meditate for years to achieve this state–this loss of the self. I just felt lost, though. Disembodied.

So I was relieved when Abby’s rapid-fire epiphanies about personhood got less profound and easier to address. Like: No, everyone doesn’t have a house. Not everyone has a bike. Everyone does have a mom, somewhere, in some way, but sometimes not with them, and sometimes they have more than one. Etc. I told her I was lucky to be her mom, and I meant it. We backed out and drove down our muddy road to the park or store or wherever we were going.

Is realizing our separateness a moment of freedom or heartbreak? I used to tell the Abby driveway story to students when we discussed Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “In the Waiting Room.” In the poem, the young speaker ricochets between the shock of seeing her separate and discrete selfhood for the first time and the realization that she is one with all the humans, in all their forms. The students loved the story about Abby. It usually took them a little longer to love the poem, but that’s okay. Bishop always won them over in the end:

In the Waiting Room - Elizabeth Bishop In Worcester, Massachusetts, I went with Aunt Consuelo to keep her dentist's appointment and sat and waited for her in the dentist's waiting room. It was winter. It got dark early. The waiting room was full of grown-up people, arctics and overcoats, lamps and magazines. My aunt was inside what seemed like a long time and while I waited I read the National Geographic (I could read) and carefully studied the photographs: the inside of a volcano, black, and full of ashes; then it was spilling over in rivulets of fire. Osa and Martin Johnson dressed in riding breeches, laced boots, and pith helmets. A dead man slung on a pole --"Long Pig," the caption said. Babies with pointed heads wound round and round with string; black, naked women with necks wound round and round with wire like the necks of light bulbs. Their breasts were horrifying. I read it right straight through. I was too shy to stop. And then I looked at the cover: the yellow margins, the date. Suddenly, from inside, came an oh! of pain --Aunt Consuelo's voice-- not very loud or long. I wasn't at all surprised; even then I knew she was a foolish, timid woman. I might have been embarrassed, but wasn't. What took me completely by surprise was that it was me: my voice, in my mouth. Without thinking at all I was my foolish aunt, I--we--were falling, falling, our eyes glued to the cover of the National Geographic, February, 1918. I said to myself: three days and you'll be seven years old. I was saying it to stop the sensation of falling off the round, turning world. into cold, blue-black space. But I felt: you are an I, you are an Elizabeth, you are one of them. Why should you be one, too? I scarcely dared to look to see what it was I was. I gave a sidelong glance --I couldn't look any higher-- at shadowy gray knees, trousers and skirts and boots and different pairs of hands lying under the lamps. I knew that nothing stranger had ever happened, that nothing stranger could ever happen. Why should I be my aunt, or me, or anyone? What similarities-- boots, hands, the family voice I felt in my throat, or even the National Geographic and those awful hanging breasts-- held us all together or made us all just one? How--I didn't know any word for it--how "unlikely". . . How had I come to be here, like them, and overhear a cry of pain that could have got loud and worse but hadn't? The waiting room was bright and too hot. It was sliding beneath a big black wave, another, and another. Then I was back in it. The War was on. Outside, in Worcester, Massachusetts, were night and slush and cold, and it was still the fifth of February, 1918.

***

Some things the students and I ask/notice/write/wonder about “In the Waiting Room”

representative and actual notes and quotes from classes, discussions, papers, musings 2014-2019

Is the speaker, the girl, the one who screams “oh” or does she hear it from Aunt Consuelo in the dentist chair? I feel like I need to understand that to understand the poem. I don’t know. It depends on how you read “from inside”...But I think it’s the Aunt…but the confusion is kind of like what’s going on with the girl in her head, with boundaries. What do you mean? Like…where she stops and everyone else ends… Her realizations are dizzying: I’m my Aunt Consuelo. I’m me. The people in the National Geographic are me. It’s all so…unlikely. That word unlikely is so unlikely. What is the “falling, falling”? And why “our eyes” glued to the cover? And the waves… I think “our” is because of her new realization of being a separate but joined human. Does she have a panic attack? I see some evidence. Waves. Over and over. The room feeling too hot. It makes me feel nervous and agitated, and the line breaks and short lines just hanging... Or an existential crisis. Definitely so much of it is in the body for her, though. What is this process called in psychology? Individuation? Or is that just adolescents? Reminds me of that quote “We are spiritual beings having a human experience…” The ‘“I said to myself” stanza is incredible. It’s the whole poem. Well…I don’t know. I mean…you need the build up and the stuff about the magazine and then the coming back to…reality? Time and space, like literally I know what she means, though. I’ve felt this same thing.

We talk about stanzaic form and line breaks…sentences and how they’re shaped.

We talk about what Bishop does and how she does it. Then we try to do it ourselves.

Note: Because the poem’s on the long side this time, I kept my classroom snippets above and resources below on the shorter side of usual. Message me/comment if you want to swap ideas around, and, always, please contribute your ideas and thoughts in the comments.

Pairings and Connections:

Question, May Swenson (the anchor poem to my last post)

Becoming Nobody Ram Dass (film, 2019)

Autobiographia Literaria Frank O’Hara

One Long Poem, Boston Review, Heather Treseler (on Bishop’s letters)

Elizabeth Bishop’s Art of Losing New Yorker, 2/26/17, Claudia Roth Pierpont

The Filling Station Bishop

And just because it’s so good, and one of my favorite scenes of human solitude and communion, this scene from Freaks and Geeks, w/backdrop courtesy The Who, “I’m One,” from Quadrophenia….Truly the best thing ever.

xo