Holding on for dear life, and also love

The Death-Grip Loves, Jane Kenyon's "Let Evening Come," and Figuring Out What's Yours to Let

At our wedding in a spruced up barn at dusk twenty three years ago, my mom gave a speech. It was rare back then for her to do something like that. Now she talks to strangers in grocery stores, bank lines, and waiting rooms. She says it’s because she’s old now and people expect that, but also because she has nothing to lose. I like the idea of seeking and making connection without needing reciprocation. It seems like something to shoot for.

At the wedding, she had on a flowing dress– also rare– and she looked very pretty, which isn’t rare at all. Crouching down to the microphone (she’s tall), she said something I thought was lovely at the time. They say if your kid is happy, you’re happy.

I heard it not as the soft warning I hear from where I stand now, but as a beautiful, one-way calculation of mother-child attachment. Primal, mathematical, umbilical. I cried when my mother said it, and got tears on my 8 month’s old head because she was coiled around me nursing just under my wedding cape, which kept slipping off her. The hormones made me not care who saw my breast. It was hard to hide anyway, because when baby Abby nursed, she insisted I suck on her finger. She poked at my mouth hard like it was a broken doorbell until I did. She was a baby who liked to give back. Fair is fair.

*

Once I got to my teens, my parents’ interventions were rare. At least that’s how it seemed at the time; I’m sure there was more happening backstage. For one thing, they both worked so much and so hard. And I’d learned by then how to make it look like I knew what I was doing. Intervening probably seemed unnecessary to the adults around me, or even to peers, I think. Meanwhile, I was often careless and generally just tested my luck, like many teens do. Maybe extra.

All of that was before I knew about the four death-grip loves: romantic; unfinished; unreturned; and the biggest and bossiest one: maternal. These loves teach you that you have to be in charge, and that you are not in charge. Once I encountered each of these loves in turn, I overcorrected from my former carelessness however I could. Sometimes by avoidance or fake bravado tactics, but usually by holding on tight.

I bristled at advice in the ‘let’ family: Let go, let it go, let it be, let’s wait and see. Deep down, I knew the wisdom of it, but functionally, I saw ‘letting go’ as an all-or-nothing proposition, as you do when you’re especially attached to people and ideas.

When you’re in one of the death-grip love modes, ‘let’ seems like a privileged dimwit. It’s a real Zelig, too: Do you mean allow? Give up? Surrender? Grant permission? Ignore? There’s leasing and releasing, relenting, forgetting, forfeiture, and sacrifice. And anyway, most of these assume ownership where there isn’t much or any. What’s ours to let? Our kid? Our desire, illness, a cricket, fox, dew, stars, or the moon? This is the bread and butter of Jane Kenyon’s poem. Let evening come? I’ll think about it.

*

Being a parent has been the tightest of all tight grips. There were periods in my kids’ childhoods when I felt like a much better parent to the kids I was teaching at school than the one I really was, at home. Teaching required the perfect balance of planning and control on one hand, and release and improvisation on the other. As a teacher, you forage and collect and hold things up to the light for examination. You respond more than react. You check in, change course, draft and revise. I foolishly thought that these skills I’d practiced for years would transfer over to my parenting when and if I had kids. Please allow me one lol.

From the beginning, I struggled with how much control I wanted and thought I needed versus how little I really have. This tension has driven most of my screw-ups and revisions over the years. At home, it was a round the clock endeavor trying to discern what’s too much involvement and what’s not enough, what’s possible and not. This was true with both our kids, but especially with our neurodiverse kid. Trying to learn how to be a good parent to him has brought me to my knees at times; in love, always, but also in humility, frustration, helplessness and shame (always about myself, never him).

At low moments, I’ve joked that my son should have had a different mother. I even chose my replacement– my friend Keira, who is gentle and equanimous instead of willful or fretful. She has a voice like a lullaby and a hundred different fun and pretty dresses. I thought maybe he should have had this punk rock Mary Poppins with a background in special ed for a mom. He got me, though, and I got him, and god do I love that kid.

*

What a beautiful baby he was. Then a happy toddler, zooming by pushing a big plastic truck in wide loops through and around other kids’ games. Singing during naptime, bouncing or making announcements during storytime, or any time. Peers and teachers were entertained, fascinated, curious, and then sometimes bothered. He’d skip over the basics and swing for the fences. It was hard for him to sit still with ideas coming in and going out so fast. He’d come in hot and then melt. It was Willy Wonka, Richard Lewis, Buddha, Maria Von Trapp, Tigger, Bart Simpson. There were meetings with school people, strained friendships, and existential crises about matter and anti-matter. You’re only as happy as your least happy kid. That’s another thing they say.

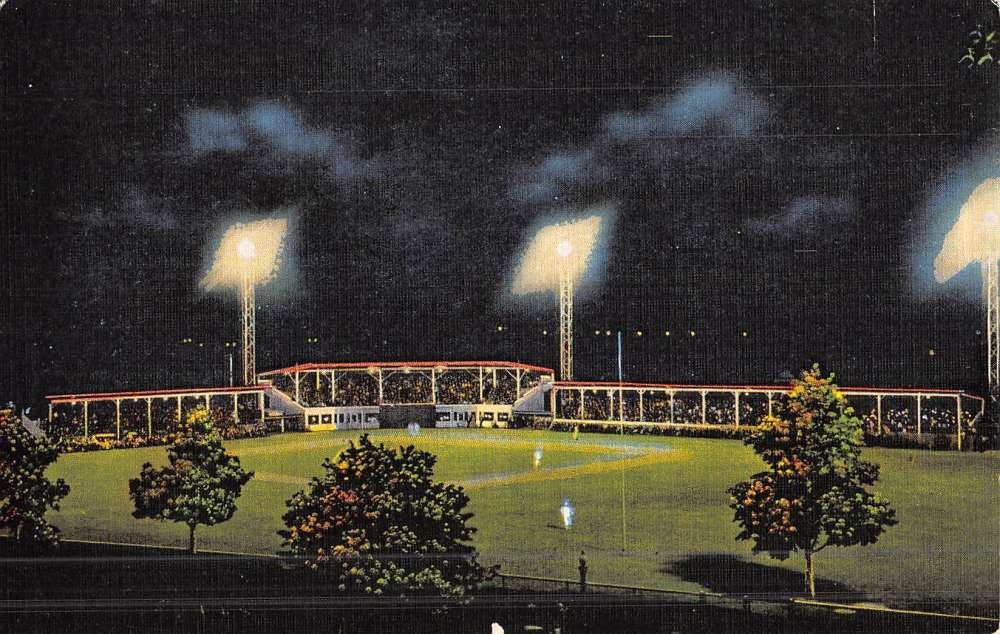

In little league he was a great pitcher, even a little savant-like, for a couple of seasons. His ragtag team had a surprising, relentless cohesion. There were computer kids, townies, hippies, kids on the spectrum, plenty of ADHD, a kid who spoke mostly French, and a sweet kid who told us he was in trouble all the time in school. Everyone had a good nickname, the coaches and parents were great, and it was just pure delight.

Those little league years gave us all a reprieve from the struggling and hypervigilance that flanked them. When he moved up a level with the older and bigger kids, it was a different ball game. At dusk during one of these games, our kid said, to no one and everyone, “Guys, look! What a beautiful sunset!” A kid walking by said “shut up” in monotone, and another snickered. I was proud that our kid just shook his head later and laughed about “shut up.” We still laugh about it when we see a pretty sky.

For years, we struggled to choose our interventions and battles at home and elsewhere, and it took us a while to stop choosing them all. To let go of trying to coach him, or ask why he did this or that (a useless question). We learned and kept forgetting and relearning the same two things: One, that his brain is wired differently. Not deficiently, and in most ways quite the opposite, but differently. And second, that navigating these challenges was a matter of skill and not will on his part. That one’s a good distinction to keep in mind for any kid.

*

I didn’t know that letting go is a thing you can at least try to cultivate with practice, or that it’s on a spectrum. Or that it’s sometimes a requirement or at least a gift to those you love the most. As in: Let their brains be their brains, let their road be theirs, and try to let your love and not fear be the driver.

In Let Evening Come, Kenyon repeats let a dozen times and it rocks us back and forth. She points to particular and inevitable beauties that are ours for loving, but not ours.

Let Evening Come. - Jane Kenyon

Let the light of late afternoon

shine through chinks in the barn, moving

up the bales as the sun moves down.

Let the cricket take up chafing

as a woman takes up her needles

and her yarn. Let evening come.

Let dew collect on the hoe abandoned

in long grass. Let the stars appear

and the moon disclose her silver horn.

Let the fox go back to its sandy den.

Let the wind die down. Let the shed

go black inside. Let evening come.

To the bottle in the ditch, to the scoop

in the oats, to air in the lung

let evening come.

Let it come, as it will, and don’t

be afraid. God does not leave us

comfortless, so let evening come.After the chanting rhythm of the first read, there’s an echo and some light baggage you carry on the second reading now that you have the last oddball (I think) stanza in your mind. That stanza has the doorknob moment: “don’t/ be afraid” and then the line about god not leaving us comfortless. I wonder about this stanza and what it does to the rest of the poem, because I think God/life does leave us comfortless sometimes. But evening will come with or without our worrying, meddling or allowances, it’s true. Crickets will chafe. Dew will collect.

The natural world rarely needs our pesky intervention, but other things do. Things will do their jobs, and we must go on and do ours. Be afraid or don’t, but figure out what’s yours to do, and then figure out what to do with it. I learned that last part from my kid. Our kids. The kids.

*

In the Classroom:

Attachment, Non-Attachment. As all this humbling was going on– rooting around to find the best ways to parent both our kids–the classroom was where I could usually find and practice balance, as I’ve said in at least one other essay. And I was happiest when I was teaching a class called Spirituality in Literature. I know the teacher’s level of happiness isn’t the point, but it was a nice side-effect. Over the years, teaching made it easier to endure hardship and celebrate joy.

When I was teaching Spirituality in Literature, relevant things would serendipitously appear: a play version of a novel we were reading; a reading or talk given by a poet or scholar. It was like when you’re in the market for a car and you start seeing that car everywhere.

Something we grappled with in the classroom that was both fraught and productive year after year was our reading, writing, and talking about the concepts of attachment and non-attachment. By that point in the semester, we would have read Siddhartha, The Stranger, a bunch of poems, excerpts from the short fiction collection A Celestial Omnibus, and from the non-fiction anthology The Enlightened Mind.

When the students and I discussed attachment, we’d discover that it seemed to apply to characters and speakers in most of the literature we read, TV shows they watched, and films we screened. The class of 10th, 11th, and 12th graders talked about caring and not caring, needing and trying not to need, and attachment theory. Isn’t attachment necessary? At what point do you know you’re too attached, or too disconnected? What about the singular attachments–to a relationship, booze, dogma, notoriety–that seesaws and catapults us up and away from any ground, far from our own moral self, or any sense of connection with other people?

And then, we’d come to non-attachment. First, we’d tease out the differences between detachment and the Buddhist concept of non-attachment, an important distinction. For students, both hearken painful experiences of aloof and uncaring social scenes, shaky or tanked friendships, being ghosted, distant romantic partners or distracted parents.

It’s scary stuff, even though teenagers are some of detachment’s most loyal adherents and practitioners; they withhold, post keep out signs, keep their distance, lie about where they’re gonna be, talk in code, etc. (And no one can shut you down and out quite like a teenager; see this Tina Fey video for reference.) It’s still scary even when the kid has chosen detachment and knows that it’s elastic and temporary, a dance, a weapon, or a strategy.

As English teachers know, using literature as our referent and anchor makes it possible to get some critical distance, to examine and dig deeper. We’d talk about the smothering, destructive conditionality that detaches King Lear from his daughters and then his reality. We’d discuss Walker’s Everyday Use and the distancing of seeing your family as symbol and signifier—a kind of folk art— rather than flesh and blood- and the loving non-attachment of the mother. During our reading of The Stranger, we’d witness our individual and collective reactions to Meursault’s slow, jerky ambulations, how he murmured when he should blurt and vice versa, and his blank version of living in the moment.

The kids would be frustrated but inspired by Siddhartha and his navigation of suffering and attachment. And if it doesn’t come up organically, I do always note that it’s only once Siddhartha has a son himself that he can really practice some serious letting go.

*

Teachers/parents/everyone: What are the difficult but worthy conversations you’ve had with students via literature; or with your kids or family via books, TV, or film?

*

Forster, E. M. (1912). The Celestial Omnibus and Other Stories. London: Sidgwick & Jackson Ltd.

Mitchell, S. (1991). The Enlightened Mind: An Anthology of Sacred Prose. HarperCollins

“Let Evening Come” from Collected Poems. Copyright © 2005 by the Estate of Jane Kenyon. Graywolf Press, St. Paul, Minnesota, www.graywolfpress.org.

you and your beautiful mom, you the luck-tester, your love death-grips (did you make those up? like the four agreements?). i love these moments especially, and seeing you so clearly in them. i love the poem, too. even the god part. solace. try try all the damn day, then let, loosen the grip. know so well how to do all this and then know nothing at all. all of us, right there with you.

So beautiful Karen. Not for nothing, the lessons you shared - learning to find the balance between what you can release control of and let the universe take care of, and what you can and should attend to to the best of your ability - reminded me a lot of Heschel’s “The Sabbath.” Reading this fantastic poem, I liked imagining that the evening in question might be Friday evening, and I think the presence of God in the last line resonates well with such a reading. You could interpret that line, rather than “God won’t let us be in a situation without comforts,” to be saying: “even if we find ourselves comfortless, God will not leave us.”