Are You For Real, Beautiful Bird?

Decoys, Poverty, Plenty, and Jamaal May's "There Are Birds Here"

On my father’s gravestone there’s an etching of a guy fly fishing, mid-cast with waders on. My father is a serious fly fisherman, even in perpetuity.

Serious fly fishermen tie their own flies. So on weekend evenings, he’d drag a kitchen chair into our TV room and set up his coffee cans and candy tins of supplies on a fold-up card table. It could have passed for the craft table of an eccentric third grade girl if you took away the beer and the ashtray. Peacock feathers, rubber eyes, hooks, animal pelt pieces, shiny threads, tiny surgical tools, a clamp spotlight, a bottle that read “fly head cement.”

Sometimes he’d turn his spotlight too bright and we’d have to insist he angle it away from the TV. We can’t see H.R. Pufnstuf. Or we’d have to ask him to stop whistling. We can’t hear what Nixon is saying, and it looks like he’s crying. Turn it up.

Most of the finished flies were preening, beautiful things in costumed reds and silvers instead of looking like the real versions of themselves. To the fish, the flashy imposter looks more like its prey than the real thing. It’s tempting to go for flash, even for fish.

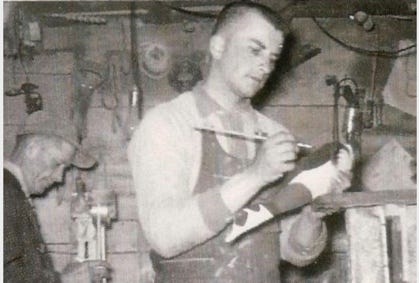

Growing up, my father worked in his father’s decoy shop in upstate NY, making the decoys that hunters would set in the water to entice unsuspecting ducks to fly over and join in. The decoys didn’t look like real ducks– just crude black and white duck-shaped cork. (Their allure relied on numbers, not flash.) By the time the real ducks realized their mistake, they were shot out of the sky.

After a time, my grandfather started making the kind of elaborately painted decoys that people put on their mantels as folk art, instead of the utilitarian kind. The family scraped by on the art ducks from then on.

***

At supper one night, my father asked me to get up early and go fishing with him on a river in New Hampshire. I was about 13. I’d go with him, I said. Just to be outside and poke around. I didn’t like fishing with him. I’d learned by then that when he was fishing, he could be (even more) bossy and rigid and forget you were just a kid. His focus was total, and it wasn’t on you. But I liked the drive with him, just me and him. And I liked that he asked me.

We got up to this old mill town and made our way down to the river. He put on the waders and toddled out up to his waist while I hopped around the rocks closer to the riverbank. He was about 15 or 20 feet upriver when he cast his line back and the fly’s hook caught my cheek a couple inches under my eye. It felt like I imagined a slap in the face would feel. Sharp, surprising, and demanding of a response you’re too bewildered to give. I touched it. Fuzzy and bulky, like a wasp.

I hadn’t been thinking about the trajectory of my father’s casting arm. I was too busy looking down at the river and its different speeds over and around things. The weeds swaying like slow motion hair in the moving water between the rocks. So pretty and green and unfazed, humoring my attention and observations. I’m gonna sway in this water. I was swaying when you woke up this morning, and I’ll be swaying in this little town boom or bust, forever.

Out in the middle of the river in his waders, I imagine my father froze for a second before he turned around and saw me holding my bleeding face. He stumbled and waddled trying to get over to me. When he did, he said oh god okay and told me to ready myself.

He wiped the slippery tear and blood mixture from my cheek and told me that the face didn’t have many nerves. He grabbed the hook with his thumb and forefinger and held his other palm against my chin. He’d have to yank the hook back out like you would out of a fish’s mouth, the reverse of how it went in. He put a bandaid on it from his tacklebox. It seemed clean. We stopped for pancakes on the way home.

Like I said, taking a hook in the cheek feels like a slap in the face probably does. But only literally. It wasn’t “like a slap in the face” despite the easy metaphor. Instead: The hook in the cheek hurt, but not as much as you’d think. It did bleed a lot. My father had been lost in his bliss, out there in his ridiculous waders. I’d made a mistake standing behind his casting arc, with the weeds and the water. He was a careless caretaker sometimes. Often.

Sometimes the literal is vivid enough. Overlooking that river, for example, is an abandoned prison.

***

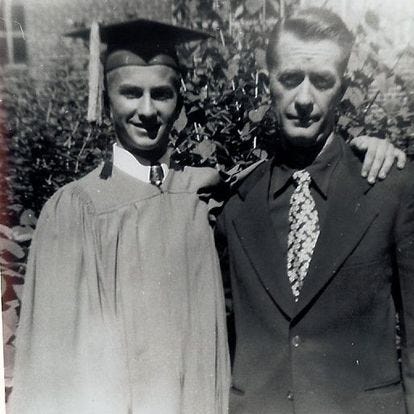

There are a few black and white photos of my father as a little boy with his family and a couple of black labs. They’re in front of their farmhouse and a beaten-down old car having a picnic? No. Just eating outside, my dad said. They did that a lot. He said it made meals not as big a deal. It lowered expectations.

***

I see a hawk, and I wonder if it’s the same hawk who’s been hanging around Mt. Auburn Cemetery, where I go just about every day. Years ago, when I needed to, I would say something about the hawk being my father’s spirit coming down to visit. Now I just say it’s a hawk. True, my father and I did both love birds. I mean he did, and I still do. But the hawk is the thing I’m seeing, and the thing I’m talking about. And it’s plenty.

***

Jamaal May’s poem is plenty, too. I love it, and I’m glad it’s here, especially now. Maybe it’s calling out imposter metaphors and their makers. Those who’ve said: Oh I will take your trauma and your history and maybe your neighborhood and make it my beauty or my penance.

Razed buildings aren’t symbols for something else. Detroit’s children playing and feeding the birds are that. Not something else. Again, plenty. Don’t doom the children.

When my daughter was a little girl, she would refer to all the birds she saw with these literal, no-nonsense descriptors. Look! she’d say, It’s a small brown hopping Arlington bird. We know the real names of birds now, but sometimes for fun we name them Abby’s way—by their actions and appearance in the moment. Hey! Blue, white, and black pointy-headed fighting bird of Watertown! Stop kicking the little brown hopping birds off the feeder. Bluejay asshole.

There Are Birds Here by Jamaal May

For Detroit

There are birds here,

so many birds here

is what I was trying to say

when they said those birds were metaphors

for what is trapped

between buildings

and buildings. No.

The birds are here

to root around for bread

the girl’s hands tear

and toss like confetti. No,

I don’t mean the bread is torn like cotton,

I said confetti, and no

not the confetti

a tank can make of a building.

I mean the confetti

a boy can’t stop smiling about

and no his smile isn’t much

like a skeleton at all. And no

his neighborhood is not like a war zone.

I am trying to say

his neighborhood

is as tattered and feathered

as anything else,

as shadow pierced by sun

and light parted

by shadow-dance as anything else,

but they won’t stop saying

how lovely the ruins,

how ruined the lovely

children must be in that birdless city.

Jamaal May, "There Are Birds Here" from The Big Book of Exit Strategies. Copyright © 2016 by Jamaal May. Reprinted by permission of Alice James Books.

Source: The Big Book of Exit Strategies (Alice James Books, 2016)

So many moments to respond to. First, H.R. Pufnstuf! xo This gave me so much insight into your dad - the outdoor not-picnics, the practical turned art details of his ducks, and the fact that he had to know that you don't have as many nerves in your face. Wow. And then there is the delightfulness of Abby's bird names. I prefer her taxonomy! this one is a beauty, Harris!!

Karen, I love this so much. Yes, the literal world is plenty, or can be. It certainly is in your writing! I love the scenes with your father, both making the flies and using them. I love the naming of birds. I love the meditation on metaphor and its limits, its dangers: the way it can seduce us into untruths. And of course I love that poem. Thank you for this. I will think and think of it. Xoxo